The Impact of Cheap Goods: How China’s Production Floods the Market

Introduction:

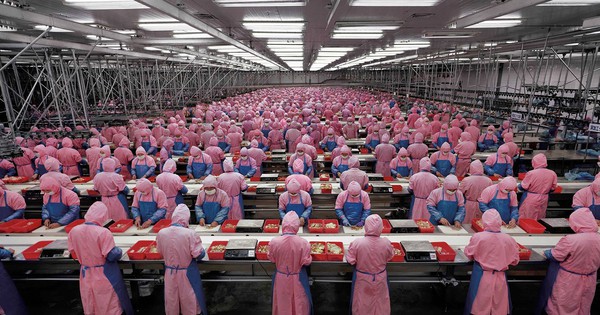

China’s emergence as a global economic powerhouse has been accompanied by a flood of cheap goods that have been both a boon and a challenge for nations worldwide. While initially hailed as a “magic pill” for low inflation, countries are now grappling with the repercussions of China’s relentless production machine.

The “China Shock” and Low Inflation

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the global economy, including the United States, experienced the so-called “China shock.” China’s explosive manufacturing growth led to a deluge of cheap goods flooding markets and helping to keep inflation rates low in many nations. However, this came at the cost of domestic manufacturing jobs.

Now, it seems that the next wave of the China shock is upon us. Determined to revive growth, China is aggressively promoting exports by ramping up production in industries like automobiles, machinery, and consumer electronics. With favorable state-backed loans, Chinese companies are flooding foreign markets with highly competitive products.

The Changing Landscape of Global Production

China’s share of global production has risen dramatically. According to World Bank data, China accounted for 31% of global manufacturing output in 2022 and 14% of total exports. Two decades ago, China’s production accounted for less than 10% and exports were less than 5%.

However, the story has evolved since then. Previously, China was the primary source of excess production, while other countries saw their factories shuttered. Now, the United States, Europe, and Japan are also investing heavily in domestic industries, safeguarding them amidst increasing geopolitical tensions.

The Challenge of Overproduction

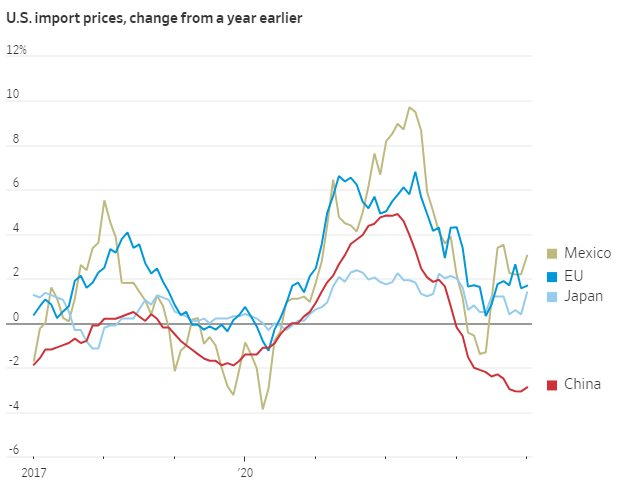

This could lead to a world flooded with manufactured goods but lacking the purchasing power to sustain demand, ultimately leading to price decline. The US, Europe, and Japan remember the early 2000s when cheap Chinese goods forced many of their domestic factories to shut down. As a result, they have invested billions of dollars to support strategic industries and impose tariffs on Chinese imports. Additionally, aging populations and persistent labor shortages in developed countries may alleviate some inflationary pressures emanating from China.

David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the authors of a 2016 paper documenting the initial China shock, remarked, “This time is a different type of China shock.”

The Unfolding China Shock

The first China shock followed a series of market-oriented reforms in the 1990s and China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. It yielded substantial benefits for American consumers, with a 2% decrease in the cost of consumer goods for each percentage increase in Chinese import penetration. Low- and middle-income individuals were believed to have benefited the most.

However, the China shock also strained manufacturers in other countries. In 2016, Autor and other economists estimated that the US had lost over 2 million jobs between 1999 and 2011 due to Chinese imports. Furniture makers, toy manufacturers, and clothing companies struggled to compete, while workers in affected regions faced difficulties finding alternative employment.

Now, the next phase of the China shock appears to be unfolding. China’s economy grew by 5.2% last year, a low figure by its standards, and is expected to slow further due to the prolonged real estate crisis impacting investment and consumer spending. Capital Economics predicts that China’s annual growth rate will be around 2% by 2030. To counter this, Beijing is pumping money into industries such as semiconductor manufacturing, aerospace, automobiles, and renewable energy equipment, aiming to export the resulting surplus.

Will China’s Strategy Succeed?

However, weak demand and excess capacity have caused China’s producer price index to decline for 16 consecutive months. Consumer goods, durable goods, food, metals, and electronics are the hardest hit.

Unlike Japan or South Korea, which shifted from low-cost production to higher-value exports, China continues to dominate low-cost sectors, even as it expands into traditional industries of advanced economies.

Rory Green, China economist at GlobalData-TS Lombard, describes China as representing “a unique challenge for protectionism.”

This protectionist approach may redirect some inflationary pressures to other regions as Chinese exporters seek new markets in less developed countries. These economies may witness the contraction of their nascent industries due to competition from China.

In conclusion, China’s transformation into the world’s manufacturing hub has come at a cost. Its flood of cheap goods has shaped global markets, sustained low inflation, and disrupted manufacturing industries in other countries. As China seeks to overcome its economic challenges, the global economy must adapt to the evolving dynamics of a resurgent economic power.

To learn more about finance and economics, visit Business Today.